“It’s certainly a good conversation starter,” Tim Sullivan said.

It certainly is that. It’s also a good conversation, period.

I had been directed toward Sullivan – a 2010 graduate and current St. Thomas Information Resources and Technologies employee – on my quest to have one question answered: Why the heck do people at St. Thomas still study Latin? A former budding-accountant-turned-Latin-major, Sullivan had some thoughts on why he – and plenty of other Tommies – still delve into a language that has slid toward neglect over hundreds of years. (Although, don’t make the mistake of thinking it’s a “dead language.” More on that later.)

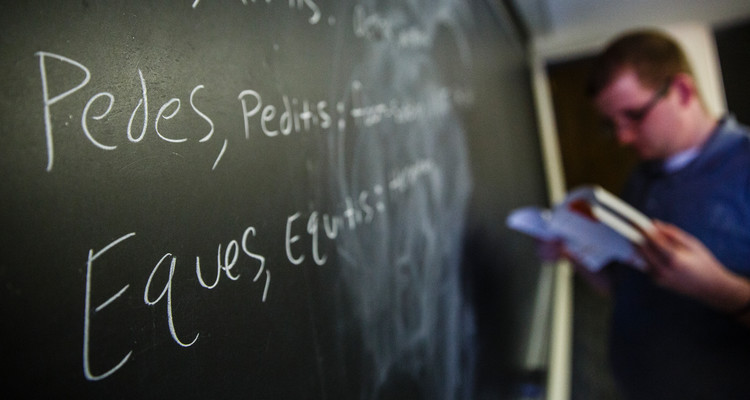

St. Thomas offers a variety of ways to approach Latin: There’s the straight Latin major or minor; the classical civilization major, which requires proficiency in Latin or Greek to supplement other courses; and the classical languages major, which requires either three or four courses in both Latin and Greek. (Students can also minor in Greek as a language.) Between the three majors there are currently about 20 students, plus several others minoring in Latin, said associate professor Lorina Quartarone, St. Thomas’ classical sections coordinator.

About half of her students are from the St. John Vianney Seminary, Quartarone said, because it requires at least three courses of Latin for all its students. (The Catholic Church’s official language is Latin.) Some, such as junior Matthew Koppinger, decide to continue on and major or minor.

“It’s just fascinating to get into a different type of structure and expressing ideas,” said Koppinger, who said he plans on parlaying his Latin into studying Greek or Biblical Hebrew in the future.

All three – professor, current student and graduate – offered insights into why they and others study Latin in today’s day and age.

It changes the way you view languages (especially English) and opens you up to learning others far better than you could without it

“I routinely hear from prior students that they never learned English until they learned Latin,” Quartarone said.

A large part of that may be because English wouldn’t exist without Latin: Depending on who you ask, English derives anywhere from between 70 and 85 percent of its words from Latin, Quartarone said. It also offers up a distinct alternative to the way English words are put together, which is a very linear style compared to Latin.

“It is a different type of language from English. English places its emphasis on the order in a sentence … and Latin works differently,” Koppinger said. “A particular Latin word may take a lot of different forms, but each of those forms may show you whether that noun is the subject of the main verb, whether it’s an object, an indirect object, an agent. Studying the different ways ideas can be expressed through modern languages and ancient languages is pretty fascinating.”

“It changed the way I wrote English, for sure,” Sullivan said. “My writing became a lot more concise and precise.”

It increases your flexibility of thinking and teaches you how to learn

Re-thinking communication building blocks through Latin gives those studying it a different way of thinking in general, Quartarone said.

“I tell them to go watch Yoda. His word order is very flexible, and that’s a feature of the Latin language students have to come to terms with,” she said. “For us an English sentence is linear and sense is determined by word order. … Studying (Latin) helps the brain to process things in a less linear fashion. It’s not quantifiable (what that does). It’s more a product … there are results of studying this language that has effects on your brain that you might not even notice but that certainly will be beneficial in the long run.”

Sullivan saw the abilities he gained in four years of studying Latin translate well into his work with IT systems after college.

“You learn to learn for learning sake, and it makes it a lot easier when you want to pick up other things,” he said. “When you learn how to learn as opposed to learning for a particular skill, you can get a broader and deeper understanding of whatever it is you’re going to be looking at. When you start studying, say in IT, what Latin is very good at is helping you see the forest and the trees. You have to understand both of those to fully grasp what you’re looking at. A lot of times people get so focused on whatever their functional task is that they lose that bigger perspective. The liberal arts like Latin can give you that: You’re learning this because it’s interesting, for the sake of learning. At the same time you get the bigger perspective, you still have to be able to deal with the particulars.”

Some St. Thomas students go on to teach Latin themselves: 2004 graduate Dan Berthiaume was honored last fall as the Latin Teacher of the Year by Classical Association of Minnesota for his work at Saint Agnes in St. Paul.

It authentically connects you with the ancient world

As students gain access to the writings of some of history’s greatest minds over the last 2,000-plus years (in their own writing, not through the filter of translation) it opens up all kinds of lessons.

“The most interesting thing to me about Latin was that when you start reading these things, you realize all the big questions people have are the same questions people asked 2,000 years ago when all these great Roman writers were writing about these things,” Sullivan said. “Even some of the novelists and playwrights were asking the same questions people are today. It’s interesting to have those connections across not only culture, but time.”

“Being able to go back and study these things in the original text helps to see just what the author was trying to emphasize. When things are translated that’s one of the things that gets lost. You can almost never translate literally,” Koppinger said.

“You’ve got such an enormous span of time, so of course what goes with that when you study the literature of any culture, people, time period, you have all of this stuff coming together: history, aspects of philosophical thought, you learn about cultural attitudes,” Quartarone said. “But the thing I like to stress the most is not just the remoteness that some people think of it. Why should I care what someone 2,000 years ago said or how they said it? The things we find remind us of just what it means to be a human being. The concerns that we have, our daily struggles. That’s stuff that unites people across any kind of boundaries, cultural, time, place.”

It’s challenging. And fun. And definitely not dead.

“The biggest motivation for someone to continue in any language, I hope, and especially Latin, is that it’s just fascinating to get into a different type of structure and expressing ideas. And to be able to do that for yourself,” Koppinger said. “Not perfectly, almost never perfectly. It’s not an easy thing, so to find something that’s difficult enjoyable – it’s nice to just try to stick with it and do the best you can.”

Sullivan got hooked after one class because it was so fun to learn.

“I just loved (studying Latin). I absolutely loved it,” Sullivan said.

Sullivan said he doesn’t actively speak Latin in his day-to-day life now, but Quartarone pointed out that he certainly could: There are monthly gatherings in St. Paul where speakers get together to converse, and year-round, week-long gatherings throughout the country where speakers come together to live and speak only in Latin. (Quartarone has attended seven of these, she said.)

“The group of people doing these things is growing all the time,” she added. “We’re embracing the language of Latin as an actual modern communitive tool.”

Quartarone said modern words are created in Latin all the time, meaning it’s a breathing, living language into 2016 and beyond.

“Most people don’t realize that Latin has been in continuous usage for more than 2,000 years,” she said. “Modern writers are writing novels in Latin. I know people who do this; you can buy their books on Amazon. There are very interesting things that have been written, not just ecclesial writing. Science fiction, fantasy, philosophical things especially.”